What if a museum felt like an adventure?

This project utilized human-centered design

methodology to develop a model for welcoming,

inclusive, and equitable antiquities museum exhibits.

The first phase examined immersive design in historic theme

and amusement park spaces as a source of inspiration for storytelling in museums. Drawing from interviews with a professional theme park designer and antiquities scholars, I developed two concepts for immersive museum exhibits.

In the second phase, I analyzed the systems that create the current status quo of antiquities museum exhibits. I identified my target user as “the curator of the future.” I reached out to students interested in making positive changes in the field of Classics, wondering how I might steer them toward implementing alternative curatorial practices. Based on these interviews I created the Handbook for Re-Curation, a guidebook for current or future curators to design exhibits that activate the senses and emotions of visitors.

For the final phase, I designed and constructed the Mithraeum, an exhibition based on the guidebook I created in phase two.

This page shares my design process and the downloadable Handbook for Re-Curation.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Loving museums, learning on-site,

& looking for the balance.

My love for the art and archaeology of the Mediterranean developed, somewhat inconveniently, while taking classes remotely in the Fall of 2020. As a college freshman facing a year of online education, my first courses about Greek and Roman archaeology captivated my imagination. When I finally arrived on-campus in Claremont, California, I pursued this new interest and officially changed my major to “Classics.”

I loved studying material culture, especially the everyday objects of the Roman Empire. I started dreaming about a career that would allow me to uncover the stories behind these objects. Interning at the Getty Villa Museum in the Summer of 2022 allowed me to learn from these objects in person for the first time.

Later, I studied in Italy and worked on my first archaeological dig at the site of Morgantina in central Sicily. I loved spending days at the museum, exploring ancient buildings, and nurturing my passion for history with new friends and great mentors. In Sicily, I spent days sketching statues in the small local museum. My favorite was a giant acrolithic goddess whose windswept drapery and extended hand made her seem miraculously caught in motion, the star of the museum since making news in 2007 when she was the subject of an international legal battle with the Getty Villa.

The trade of looted antiquities has supplanted the collections of most American antiquities museums. Now, many countries are requesting stolen objects back, a process I learned was called

Repatriation.

While I loved these museums, I knew the goddess belonged at Morgantina. In the empty spaces left after repatriation, I began to imagine something new.

Questioning the Status Quo

As a student of Roman archaeology, this room in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is incredibly exciting. As a design student, and as a person, a few sources of discomfort stand out to me.

Level 1:

INACCESSIBILITY

Some aspects of the room act as barriers to interacting with the material including

-

English-only labels with few language accessibility resources

-

Very little seating available for guests with disabilities.

-

Available seating is located far from the art

-

Museum visitors describe these rooms as "silent", "cold", and "surveilled."

Level 2:

UNENGAGING

If visitors are able to get past these aspects of inaccessibility, they may be disappointed by what they read. The readability of the labels in this gallery is far beyond the reading level of the average American. Most visitors find it difficult to engage with gallery text, often skimming or skipping when faced with content that seems like it was not written with them in mind.

Museum visitors describe these rooms as "long", "impersonal", and "confusing."

We connect with moving personal stories that prompt us to imagine the rich lives and experiences of other people. Gallery labels that provide information without story fail to keep visitors engaged.

Level 3:

PROVENANCE

Where did this

all come from?

Along with the physical discomfort of inaccessible spaces and the mental discomfort of unengaging gallery text, antiquities galleries also present the moral discomfort that arises from questions about provenance.

Many American antiquities museums knowingly or unknowingly hold objects in their collection that have entered the United States illegally.

Through looting, smuggling, and obfuscation of provenance these objects entered the circulation of American collections. Repatriation refers to the return of artifacts and artworks to their original countries, due to legal pressure or moral obligation.

Like surveillance, the presence of illegally-acquired antiquities negatively impacts the experience of visitors depending on their backgrounds.

There is no effective way to address one of these problems without considering all of them.

When attempting to make museums more equitable, it is not enough to add accessibility resources if the content museums are trying to make more accessible is unengaging. Museums will still fail to be equitable spaces if engaging historical narratives center around objects that perpetuate colonialist narratives.

In order for the museum to become more equitable, it must address all three of these issues. What would a welcoming, engaging, and object-less exhibit look like?

What opportunities

arise when objects leave museum collections?

PHASE I :

CONCEPTUALIZING

When imagining my dream museum I was inspired by my love of themed entertainment.

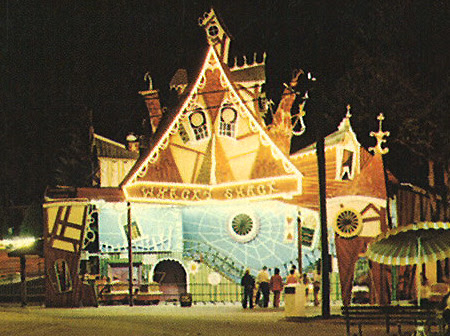

Whacky Shack(1969),

Waldameer Park, Pennsylvania

exterior, layout, and designer Bill Tracy

I loved the idea of applying innovative, and sometimes strange, multisensory storytelling techniques to historical education. Game and themed experience designers use environmental storytelling to incorporate story details into all aspects of an experience, this means designing narrative information into the objects and buildings surrounding users.

I researched the history of experiential design, looking at how multimedia elements have been combined and reused over the past century to create immersive stories. Australian artist and researcher Joel Zika has spent his life documenting the history of forgotten amusement attractions, pointing out a lack of documentation for these incredible forms of multimedia art. Zika focuses on the history of early “dark rides”, small, sometimes portable, rides that centered around a thematic journey.

Dark rides by designers like Bill Tracy were relatively low-cost attractions with a small footprint, built to service large numbers of guests per hour. Their exteriors were eye-catching, intrictely designed to draw guests in and spark their curiosity.

Using the elements of light, sound, and touch these designers welcomed visitors into a multisensory journey, engaging the curiosity and imagination of people of all ages.

This research led me to consider ride design as a source of inspiration for museum exhibits. I wondered what these rides would be like if, instead of recreating haunted houses and ghost trains, they took visitors through the Roman emperor Nero’s lavish imperial abode or an Etruscan necropolis

“These objects are our talismans. But they aren't the history…

They're the gateways for us to reflect on what it was like to have been in that time period.”

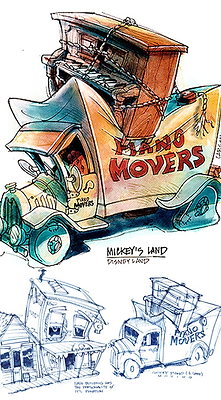

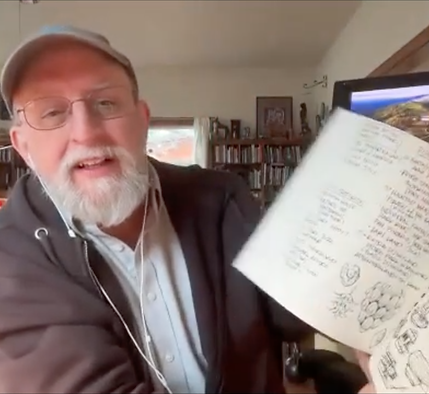

After decades of work as an amusement park designer, Don started wondering about the educational applications for immersive environmental storytelling. He understands the way to communicate engaging, emotional, and personal stories using theme and amusement park technology and he wishes he had the opportunity to apply his knowledge in the museum space.

I had the incredible opportunity to meet and work with Don during my design process. I was delighted to discover that we shared many of the same ideas about museum design and immersive experience. He saw museum objects in the same way I did...

On his YouTube channel Don makes videos demonstrating his own design process and teaching the technologies and techniques of theme park design. In 2020 he made a series designing a dark ride which shared everything from concept sketches to a completed VR walkthrough of the ride.

Utilizing his techniques from these videos I developed two concepts for immersive museum exhibits.

Concept 1

Sappho's Somatopia

This exhibition proposal was developed as a final project for my Fall 2023 course in advanced Ancient Greek translation, based on my own translations of Sappho’s poetry.

I began to imagine an exhibit that could do what Sappho’s poetry does: immerse us in physical experience. Through trompe l'oeil wall paintings, fabricated set pieces, and projection techniques, visitors would be put inside some of her most well-known poems. The goal was to design an exhibition that would be exciting and engaging for visitors of all ages and backgrounds.

I sketched up some ideas inspired by early dark rides, Don Carson's design videos, and other theme park concept art. I drew each room according to the specific sensory details in Sappho's poetry.

Asking the Experts

An interview with Etruscan tomb scholar Amelia Eichengreen

Scholar Amelia Eichengreen was excited to discuss the potential for an immersive exhibition that put visitors inside Etruscan necropoleis. We discussed our love of well-researched immersive exhibits like the VR experience at the Domus Aurea in Rome and complained about their well-intentioned but poorly researched counterparts.

I asked about the sensory experience of being in an Etruscan necropolis and Amelia explained that, while the sites are currently unchanging archaeological parks, necropoleis were incredibly active frequently changing spaces.

"They were loud spaces. People would have been visiting their dead relatives in what was basically an active construction zone."

When visiting a necropolis in ancient times, people would have heard the sounds of quarrying and cutting rock and smelled the dirt and dust. People frequently visited and added to family tombs.

We discussed what we would want visitors of all ages to gain from an exhibit about Etruscan tombs. The primary goal would be to get visitors interested in the Etruscans. We would also want visitors to understand that archaeological material from necropoleis provides much of what we know about the Etruscans and that these necropoleis were ever-evolving spaces.

Concept 2

Journey into the Etruscan Tombs

The Etruscans inhabited Etruria in ancient Italy. Despite their key role in early Roman history, they usually go unrecognized in discussions of ancient Mediterranean civilizations.

Learning about the Etruscans inspires curiosity about the civilizations that existed alongside ancient Rome, leading to questions about how and why certain histories are prioritized over others.

Much of what we know about the Etruscans comes from their Necropoleis, thousands of tombs arranged in a city-like pattern. Many were elaborate, with wall paintings and sculpted decorations that reflected the wealth of the entombed individuals.

Visiting the Cerveteri Necropolis during my time in Rome allowed me to explore the incredible wandering streets and cavernous tombs of the ancient civilization. It sparked my interest in Etruscan history and I found myself wishing I could offer the same experience to kids in my hometown across the world. I once again found myself imagining a traveling dark ride, like those in of old carnivals, as a vehicle for Etruscan education.

What would it take to make these ideas a reality?

PHASE 2 :

STRATEGIZING

Defining my user, a museum curator ready to experiment

There is a future where antiquities museums are welcoming, engaging, and educational without featuring objects of questionable provenance. For exhibits like this to jump out of fantasy and into reality, curators must be willing to experiment with new and multisensory forms of education.

Design projects typically center around a user profile, the imagined or real person who can benefit from new designs. While I initially imagined my users as a diverse group of visitors, examining the systems that drive change within museums led me to imagine a new user: a motivated young changemaker willing to approach these problems from the inside. I was designing in the hopes that one day my users could generate their own ideas for immersive exhibitions, ones that I would never come up with on my own.

USER:

THE CURATOR OF THE FUTURE

Currently pursuing a degree in Mediterranean archaeology with an interest in becoming a museum curator and a desire to make positive change

(in Classics and in the world).

Asking the Users

An interview with Carrie, a Classics Ph.D. Student.

Many of my friends and peers matched my user profile. During my time studying classics I met others with similar interests who could likely become curators at major museums one day. For feedback and testing on this project, I reached out to friends at universities across the country and asked them about their perspectives on museum design.

One of the people I was most excited to speak with was Carrie, a current Ph.D student focusing on the archaeology of the Roman empire. Like me, Carrie had an undergraduate internship at an antiquities museum and studied at the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome. She has worked in the field at multiple Roman-era archaeological sites and demonstrates an unparalleled passion and excitement about the material.

My interview with Carrie helped deepen my understanding of my user, understanding what existing ideas future curators have about museums and curation. First, we discussed her journey in the field, from her earliest interest in high school Latin to the process of applying for her Ph.D. program.

During our conversation, Carrie described how she feels while she is in a museum. She sees museums, as almost a holy place, with behavioral expectations and an environment of reverence similar to being in church.

"“There's a really strange thing about museums where you almost have to acknowledge the specialness of what's inside, through your body language”."

We talked a lot about behavioral expectations in academic spaces: the unspoken rules that govern how we behave in classrooms and among peers and professors. She often feels like she needs to leave her personality at the door in order to succeed in the classroom.

“I always think of, like, my scholarly presentation of myself as putting on a show of it. It's the person I become, or I assume the identity of when, for example, I'm writing a paper, or when I'm giving the presentation.”

I was shocked to learn that she sees this scholarly voice as the ideal, seeing her personality as limiting her work. In her sixth year of studying Classics, she described her scholarly voice as a set of conditioned academic habits that have allowed her to succeed in her classes and early professional opportunities.

These habits include:

-

formal speech and academic vocabulary,

-

adopting the speech patterns and demeanor of professionals,

-

avoiding topics like political and personal beliefs,

-

insider speech and name-dropping,

-

and an emotional distance from the material.

When speaking about how her personality and emotions effect her approach to the material, Carrie said

"It's something that I'm still trying to get past.”

Carrie's experiences demonstrate how potential curators are encouraged to adopt an academic identity that runs contrary to their individual voices, which reinforces the status quo of museum curation over time. If all curators feel pressured to adopt the "identity" of an antiquities curator, very few new voices may enter the museum curatorial space. With this homogenization the staus-quo is reinforced and along with it, the tiers of inaccessibility in the museum.

Common threads

Carrie wasn't the only one of my interviewees to identify this divide between their serious academic voice, and their "personality." I spoke to others who said they felt discouraged from bringing their personal voices into academic spaces.

When I talked with multiple undergraduate design students from schools across the United States, I noticed that all of them reported feeling a contradiction between their academic interests and personal values.

In the Introduction I outlined a few problems with the status-quo of antiquities museum curation, including the inclusion of illegally and immorally aquired objects in exhibits. The connection between museums and their complicated histories of colonialism was a topic that all of my interviewees expressed discomfort with. The stigma and fear around these conversations is the reason I am not sharing names or details of these intervewees indiviudally, as most of them feared they would be professionally or academically ostracized for sharing their feelings.

For a few, especially non-white students, this tension made it difficult to consider a career in museums. While they loved studying history and enjoyed visiting antiquities museums, these Classics students felt like working in an antiquities museum in America would feel like a betrayal of their personal values.

"I always thought that museum work would be great, but it would be better if I could be doing work that was increasing accessibility."

In this way, potential museum curators, especially those who are not white, are steered away from working in the museum space due to the status quo of exhibit design.

Continued Concepts:

Asking the Users

Carrie feels most connected to history when interacting with personal stories. She does this by reading ancient Greek and Latin funerary inscriptions saying

"My engagement with funerary stuff has just kind of like, exponentially grown. As my knowledge of Greek and Latin has grown. If I didn't know Greek or Latin, I don't know what I would do in an ancient Museum,”

This comment highlighted how Carrie, as a potential museum curator, has a radically different experience in antiquities museums than the average visitor. Her years of education in Ancient Greek and Latin allow her to interact with the firsthand accounts of ancient people in a way that is complex and emotionally moving.

Carrie recognized the importance of storytelling in the museum but had not considered how these stories could be accessed without extensive knowledge of ancient languages.

When I asked Katie how she would make funerary monuments accessible, she paused for a while. Despite calling herself “uncreative” and never previously considering alternative curatorial methods for epigraphy, she proposed a captivating and hilarious idea for an interactive exhibit.

BUILD A BURIAL:

"It could almost be like a build-a-bear museum... Because like, I think that what I love so much about the funerary monuments... I would really want interactive aspects of an ethnographic museum to be was be the process taking something that's very generalized, and individualizing it and making it special and one’s own."

Carrie feels most connected to history when interacting with personal stories. She does this by reading ancient Greek and Latin funerary inscriptions saying

"My engagement with funerary stuff has just kind of like, exponentially grown. As my knowledge of Greek and Latin has grown. If I didn't know Greek or Latin, I don't know what I would do in an ancient Museum,”

This comment highlighted how Carrie, as a potential museum curator, has a radically different experience in antiquities museums than the average visitor. Her years of education in Ancient Greek and Latin allow her to interact with the firsthand accounts of ancient people in a way that is complex and emotionally moving.

Carrie recognized the importance of storytelling in the museum but had not considered how these stories could be accessed without extensive knowledge of ancient languages.

When I asked Katie how she would make funerary monuments accessible, she paused for a while. Despite calling herself “uncreative” and never previously considering alternative curatorial methods for epigraphy, she proposed a captivating and hilarious idea for an interactive exhibit.

Although it sounds absurd, Katie’s idea could evoke the strong emotions and personal connection necessary for a moving and memorable museum experience.

SUMMARY:

POV: CARRIE

I interviewed Carrie, a PhD student studying Roman Archaeology. I was amazed to discover Katie had a fun, creative, and absurd idea for an accessible museum exhibition. I wonder if this means other future curators have ideas for object-less exhibitions. I aim to encourage them to embrace these ideas.

My conversation with Carrie made me wonder if other Classics students had ideas about interactive and immersive exhibitions.

I showed each of my interviewees a video an interactive exhibit in a science museum and asked them what it would look like if this kind of exhibit was made for their area of study.

Every person I asked had at least one idea for an interactive, immersive, and engaging exhibit without objects.

THE ATTALID DEDICATION

“I think it would be really cool to have like a, you know, a video or some such thing like that you can like kind of like one of those like touchscreen, whatever, that you could see it because those two statues are meant to be on the same display”

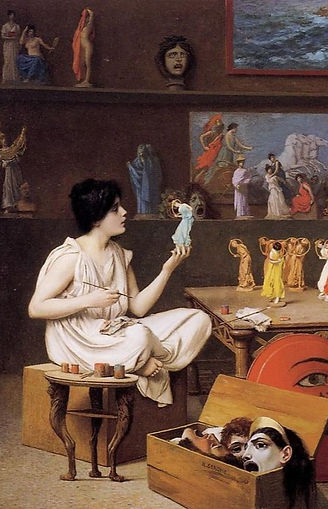

GREEK POLYCHROMY

“a workstation where people can get like little like figures of statues and like painting them, you know, because they're not white anymore. And like, even in museums, they don't tell you that often.”

THE ROSETTA STONE

“I would like to have like a hologram of the Rosetta Stone. So people can like, zoom into different parts and like, deal with it that way.”

These interviews showed me that there is dormant curatorial creativity in everyone. with the right prompt I believe that curators can act as collaborative designers, working from their own expertise to create exhibits without objects.

Creating a tool for future curators

After interviewing friends and peers about their experiences in Classics, perception of museums, and imagined exhibitions, I put together a guidebook to leave them with. It addresses the need for alternative curatorial practices and explains the potential benefits. The final section is a series of worksheets designed to help readers develop their own multisensory exhibit. It prompts them to imagine how each sent could become a part of the exhibit, also asking them to develop the key takeaways for visitors. It ends with a list of more expansive prompts, ranging from “make everything out of paper” to “add a slide.” Working from the feedback and ideas of my interviewees, I wanted to create something that could spark excitement, even for those who are not planning on becoming curators.

How can I put these

ideas into effect?

PHASE III :

ACTUALIZING

Demonstrating the possibilities of immersive exhibit design

I wanted to prove that it was possible to do something like this with little financial investment. When deciding what my exhibit was going to be, I knew I wanted to create something low-cost and small-scale.

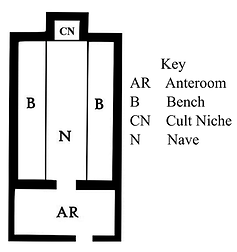

I drew up plans for a few exhibits, but the Mithraeum was obviously the most natural thing to put in the small, dark room I had access to in the Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity, which served as the design center for the Claremont Colleges.

The first time I learned about mithrea, these strange underground archaeological sites, I was at home in Hawaii taking an online class called Roman Art and Archaeology. Hearing about the mysterious cult was food for my imagination. In Classics, Mithraisim is referred to as a “mystery cult” with private initiation ceremonies and no written accounts of their beliefs.

I knew that if I wanted to truly recreate the site, I would have to consider the colorful paints and the decoration of the benches, aspects of the site and ritual that had no archaeological remains.

I visited two intact mithraea during my study abroad program in the Spring of 2023. My experiences there informed my approach to the recreation.

The plot of the experience put visitors in the shoes of futuristic "experience detectives" sent back in time to investigate the ritual activity of Mithraisim

I constructed my exhibit primarily out of materials from the design center. I created fake stone walls using foam core board, a painted ceiling out of draped fabric, and interior benches using rolling tables. Together, they blocked out the light and recreated the darkness of a real underground temple.

I combined archaeological evidence from mithraea across the Roman empire, recreating votive offerings out of foam clay and incorporating a mithraic altar that was recently sold at auction.

By putting these items in the recreated context I hoped to make them more powerful learning tools. I loved being able to see each item next to each other and within the layout, lighting, and environment of the room. Aspects of smell and taste were also considered, as I included the historically accurate food that was an essential element of mithraic ritual.

The painted relief in the cult niche was a 1:1 recreation of a mithraic relief in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. I believe when compared to the well-lit white display in VMFA, my exhibit in the vault offers viewers a greater

understanding of mithraic practices and iconography.

From the Mithraeum

Images + Walkthrough Video

Inspiring new curiosity

Inviting new voices.

It was so rewarding to bring my friends, family, and professors into the mithraeum and watch them expore something I created. It was one of the first times I felt like I was truly able to share my love of Roman archaeology with them. For once, it felt like they were just as excited as I was.

I shared my work with my peers in Classics in person and over video. Many of them had been in mithraea with me and I was delighted to hear that they found the exhibit exciting, accurate, and inspiring.

“It reminded me of the mithraeum in Ostia.

It's so interesting that it was so dark but your mind filled in the space in the real mithraeum I think you were able to capture that.”

“That was awesome!!! I would love to see something like this in every museum.”

“I think, maybe this is me, I love museums but it’s kind of unfortunate that everything is stuck in this loop of aquire things and put in case...

I always thought that museum work would be great. But it would be better if I could be doing work that increases accessibility.”

My goal was to create something that made an equitable and welcoming antiquities museum feel achievable and hearing students who previously expressed frustration with the museum environment become excited about this project was a big success. I hope as I am able to build upon these ideas and share the process of re-curation with other interested students and professionals, more people can begin to imagine their dream museums.

RESOURCES

Acknowledgements

This project was only possible due to the support and guidance of Fred Leichter, who encouraged my strange ideas and pushed me to share them with the world.

Thank you to Asha Srikantiah, Shannon Randolph, Brian Keeley, and my incredible Classics advisor Michelle Berenfeld. Also, thank you to Jody Valentine for endlessly inspiring me.

Thank you to my interviewees! Your quotes and ideas brought this project to life.

Thank you to the shining star Cece Malone. I couldn't have done this without you. I am forever grateful for your friendship and dynamism. You always make me better.

Thank you to my weird friends. This project was fueled by many late-night conversations with Quin, Alex, Lilly, Nick, Tali, Will, Anja, Dylan, Aden, Eleanor, and Hazel. Thank you to Ryann Liljenstolpe, who listens to a lot of my ramblings and continues to inspire me constantly. Thank you to Jordan James for helping me construct and deconstruct the Mithraeum and for everything before and after. I am so lucky!

Thank you to my friends and coworkers at the Center for Asian-Pacific American Students and at the Hive. You guys lightened the load.

And finally thank you to my mom, who has always been my number one supporter. Thank you for always advocating for my education and helping me through the tough times. Everything I do is thanks to you.

Bibliography

Arievitch, Igor M. Beyond the Brain: An Agentive Activity Perspective on Mind, Development, and Learning. 1 online resource vols. Bold Visions in Educational Research; v. 57; Volume 57. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: SensePublishers, 2017.

Batacharya, Sheila, and Yuk-Lin Renita Wong. Sharing Breath: Embodied Learning and Decolonization. 1 online resource vols. Cultural Dialectics. Edmonton, AB: AU Press, 2018.

Baum, Merriam Sharon B. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide, Fourth Edition. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

Chae, Yung In. “White People Explain Classics to Us.” Medium, October 9, 2020.

Eccleston, Sasha-Mae, and Dan-El Padilla Peralta. “Racing The Classics: Ethos and Praxis.” American Journal of Philology 143, no. 2 (2022): 199–218.

Hill, Mary C, and Kathryn K Epps. “The Impact of Physical Classroom Environment on Student Satisfaction and Student Evaluation of Teaching in the University Environment” 14, no. 4 (2010).

Holtorf, Cornelius. “‘Pastness in Themed Environments.’ In: A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces (2016), Pp. 31-37. Edited by Scott A. Lucas. Pittsburgh: ETC Press.”

Jackson, Kathy Merlock, and Mark I. West. Storybook Worlds Made Real: Essays on the Places Inspired by Children’s Narratives. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2022.

Kelley, Robin D. G., and Aja Monet. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Twentieth anniversary edition. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2022.

Lee Yunhee. “Narrative Modeling and Cultural Literacy in the Storyworld: A Quest for Meaning.” Language and Semiotic Studies 9, no. 4 (2023): 561–75.

Lukas, Scott A. A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon/ETC Press, 2017.

Lukas, Scott A. The Immersive Worlds Handbook: Designing Theme Parks and Consumer Spaces. Burlington, MA: Focal Press, 2013.

Macrine, Sheila L., and Jennifer M. B. Fugate. Movement Matters: How Embodied Cognition Informs Teaching and Learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022.

McCarty, Matthew M., Mariana Egri, and Aurel Rustoiu. “The Archaeology of Ancient Cult: From Foundation Deposits to Religion in Roman Mithraism.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 32 (2019): 279–312.

Merriam, Sharan B., Rosemary S. Caffarella, and Lisa M. Baumgartner. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

MUF Architecture. “Reimagining Children’s Museums.” In Muf Architecture/Art, 2013.

Nathan, Mitchell J. Foundations of Embodied Learning: A Paradigm for Education. New York, NY: Routledge, 2022.

Poser, Rachel. “He Wants to Save Classics From Whiteness. Can the Field Survive?” The New York Times, February 2, 2021, sec. Magazine.

Rahimi, Farzan Baradaran, Beaumie Kim, Richard M. Levy, and Jeffrey E. Boyd. “A Game Design Plot: Exploring the Educational Potential of History-Based Video Games.” IEEE Transactions on Games 12, no. 3 (2020).

Renner, Nancy Owens. “Free to Explore a Museum: Embodied Inquiry and Multimodal Expression of Meaning.” University of California, San Diego, 2013.

Ryder, Bethan. “‘Part-Science Lab, Part-Playground’: How Kids Made Museums Take Fun Seriously.” The Guardian, January 19, 2020, sec. Culture.

Soligo, Marta, and Brett Abarbanel. “Theme and Authenticity: Experiencing Heritage at The Venetian.” International Hospitality Review 34, no. 2 (2020): 153–72.

Steele, Chauncery D. IV. “The Morgantina Treasure: Italy’s Quest for Repatriation of Looted Artifacts Notes.” Suffolk Transnational Law Review 23, no. 2 (2000 1999): 667–712.

Stevens, Lorna, Pauline Maclaran, and Stephen Brown. “An Embodied Approach to Consumer Experiences: The Hollister Brandscape.” European Journal of Marketing 53, no. 4 (January 1, 2019): 806–28.

Wiener, Anna. “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art.” The New Yorker, February 10, 2022.

Williams, Rebecca. Theme Park Fandom: Spatial Transmedia, Materiality and Participatory Cultures. 1 online resource vols. Transmedia (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Yaffe, Deborah. “The Color of Classics.” Princeton Alumni Weekly, September 30, 2021.

Zika, Joel. “Dark Rides and the Evolution of Immersive Media,” 2018.